Disaggregating data helps replace racist policies with anti-racist ones

As communities across the United States and throughout the world work through the pain and anger over the latest tragic display of racist, state violence against Black lives, we redouble our efforts to change policies that perpetuate injustice.

Racist law enforcement policies lead to racist actions by law enforcement officers. “Systemic” or “structural” racism is so-called because it is built on and adds to a system of racist policies that permeate every aspect of life in the United States of America. It is through changing that system—replacing racist policies with what Dr. Ibram Kendi calls “anti-racist” policies—that racist actions can be curtailed and racist thinking can be overcome.

One often overlooked way in which racism manifests itself in our policies is through our use of data.

This is not a small matter: the chief reason to collect data is to shape policy and programs. Data defines problems and solutions and is used to determine who is deserving of resources and how much each group is allocated. All too often, even in Hawaiʻi, Native Hawaiians are unseen in state program data. This invisibility masks the needs and contributions of Native Hawaiians and keeps them from having a say in decisions about program goals, budget, design or evaluation. Two aspects of collecting and using data are key here.

Disaggregated Data

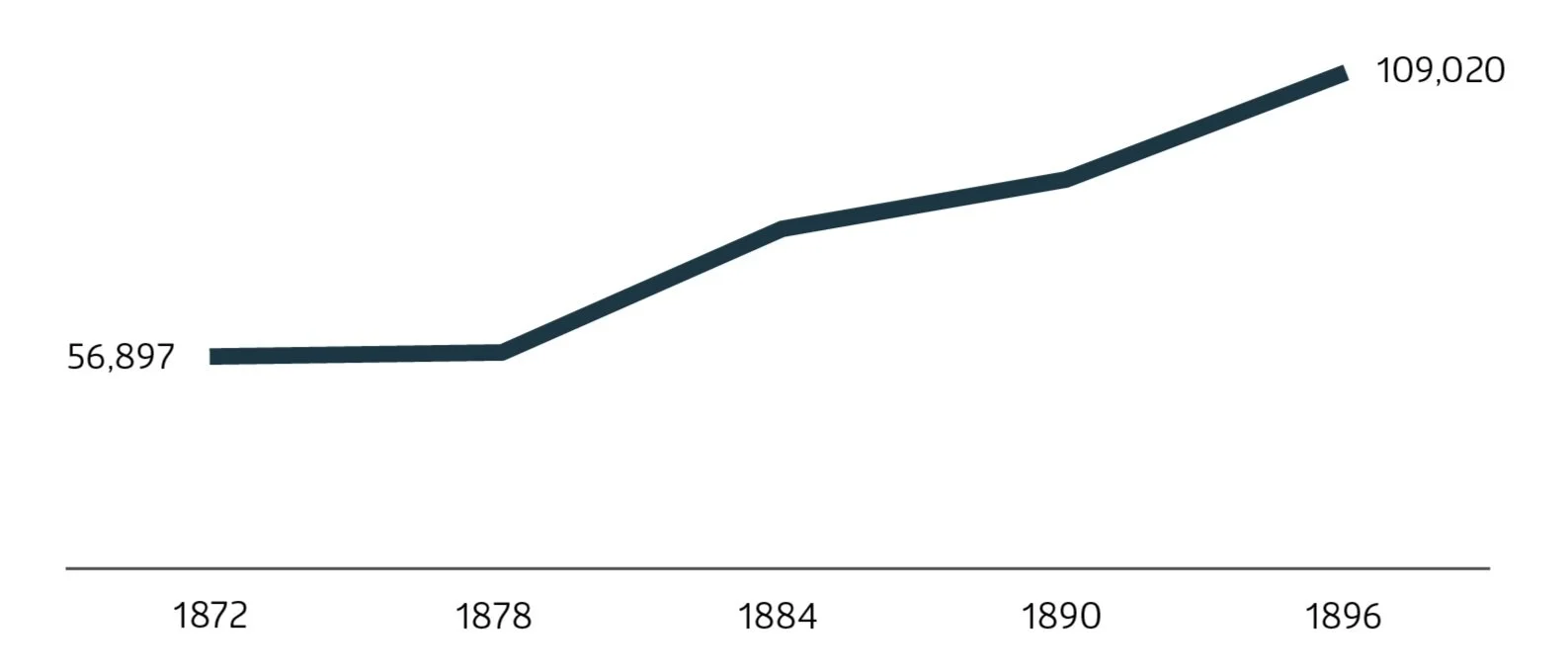

Disaggregated data means that information is broken down into meaningful component parts. It might be data specific to ethnic, age, gender, geographic, or other characteristics that render it meaningful for various uses. A striking example charts Hawaiʻi’s population between 1872 and 1896. The population of Hawaiʻi in 1778 when Captain Cook arrived was estimated to be 300,000. Due to disease and systematic disenfranchisement imposed by white colonists, the population had shrunk to less than a fifth of that size by 1872. However, between 1872 and 1896 the population nearly doubled.

Figure 1. Total Population of Hawaiʻi, 1872–1896

Figure 1. Hawaiʻi’s population appears to be thriving between 1872 and 1896, as its population nearly doubled over the course of just 24 years.

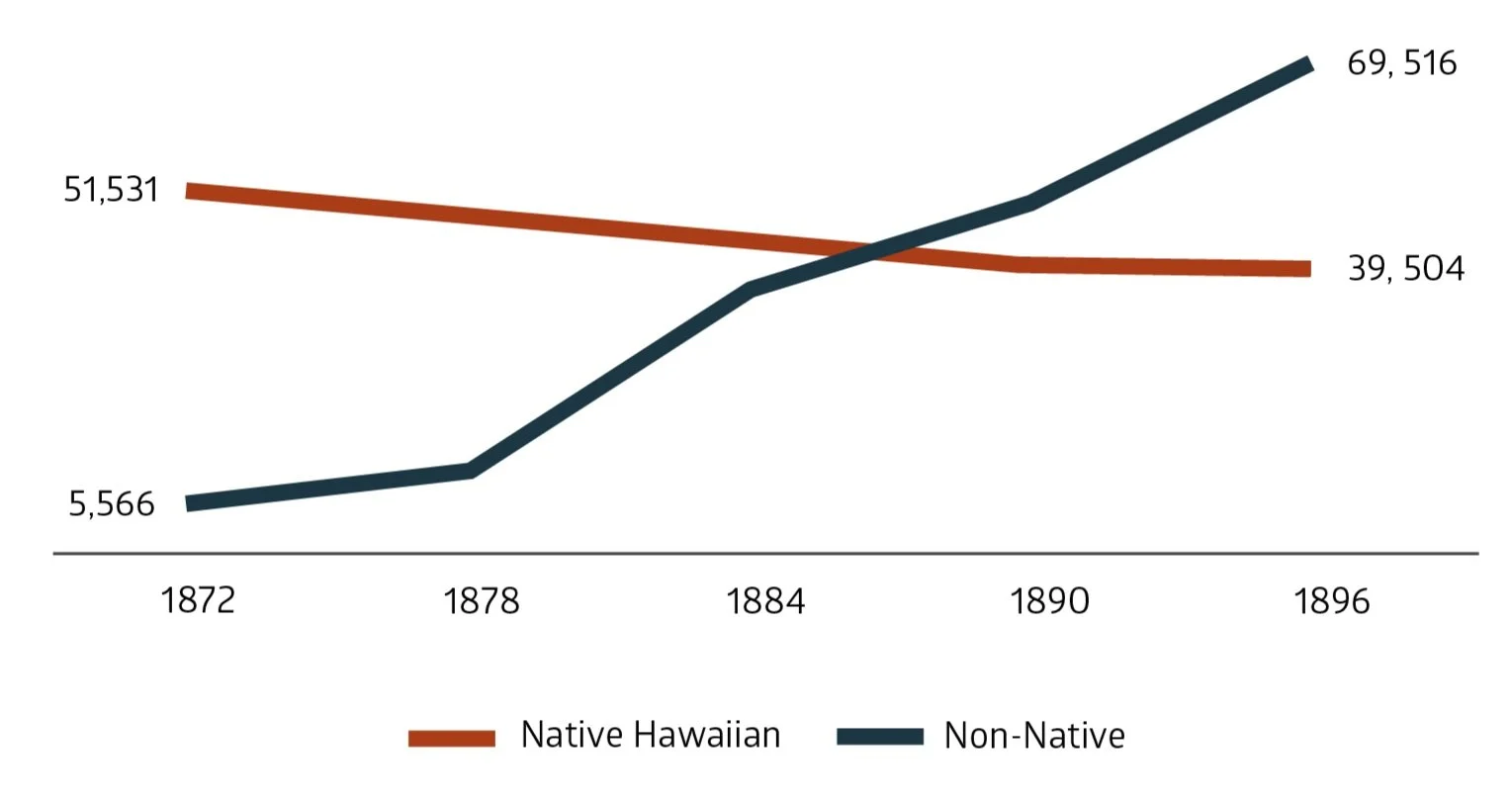

Without disaggregated data, this would appear to describe a remarkably positive rebound. However, when Native Hawaiians are made visible through disaggregated data, we can see that these statistics instead describe the continuing history of decimation. The number of Native Hawaiians continued to decline even as the overall population again expanded in the late 1800s. By 1893, when a group of white businessmen illegally seized the Hawaiian Kingdom, fewer than 40,000 Native Hawaiians were left.

Figure 2. Native vs Non-Native Populations of Hawaiʻi, 1872–1896

Figure 2. Disaggregated data shows that the Native Hawaiian population continued to shrink, while Hawaiʻi was increasingly populated by newcomers.

Population data source: Robert C. Schmitt, Demographic Statistics of Hawaii: 1778-1965

Self-Determination in Data

Self-determination (sometimes “decolonization”) in data means reclaiming the purpose and value of data collected, analyzed and used by and for native peoples (or others of special interest). Too often, data reflects only illness, weakness, or needs because those are the filters applied by policymakers and funders who are trying to solve problems.

But indigenous peoples (and other groups with special needs) have inherent strengths and points of view that should be used to mold priorities and programs. Putting data decisions into the hands of the people described by that data acknowledges their strengths and puts them in control of what data is gathered, how it’s interpreted and what it will be used for.

Disaggregating data and self-determination are both needed in order to redefine problems and strategies that lean on Native Hawaiians’ strength, resilience and wisdom to solve problems. The shortage of thoughtful and specific data can leave both problems and solutions unidentified.

The State of Hawaiʻi could take a meaningful step toward dismantling racist policies and replacing them with anti-racist ones by establishing a universal policy of collecting disaggregated data for all its programs, and then using the data in partnership with the groups represented. Doing so would empower these groups to define the strategies most likely to promote well being for themselves, and provide policymakers with solutions already accepted by impacted communities.